As humans, we perceive space and time as a seamless, continuous flow. This perception leads us to believe that continuity—and perhaps even infinity—is a fundamental aspect of nature. However, some scientific theories challenge this assumption. For example, string theory posits that the universe’s fundamental components are tiny, vibrating strings, where different vibrations define different particles. Similarly, loop quantum gravity suggests that space itself is made up of discrete “grains,” implying that reality might not be as continuous as it appears.

Why should this intrigue us, Machine Learning Surgeons? Because while we may experience continuity, machines do not. Machines operate strictly within the realm of discrete and finite data types, from bits and bytes to floating-point numbers. This disconnect raises a crucial question: How can machines represent signals that seem continuous to us?

Consider the spikes generated by neurons in the brain. While neuronal activity appears continuous from a biological perspective, it can be interpreted as a series of discrete events—spikes or pulses. To model this activity on a machine, we sample these spikes at fixed intervals, effectively converting a seemingly continuous signal into a discrete representation. The choice of how finely we sample (and which data types we use) impacts the fidelity of our representation, affecting everything from signal reconstruction to downstream machine learning models.

This brings us to the core challenge: quantization—the process of mapping continuous values to discrete ones. Let’s explore how this translation from the continuous to the discrete world shapes our data types and impacts machine learning performance!

What is Quantization: The Anatomy of Precision#

In the natural world, many signals—such as sound waves, light intensity, or even time itself—are (perceived) continuous. However, machines, by their very nature, operate in a discrete framework. They deal with bits, bytes, and finite representations of data. This fundamental limitation means that to store and process real-world signals, we must first translate them into a form that machines can understand. Enter quantization.

Quantization is the process of mapping a continuous range of values into a finite set of discrete levels. Think of it as breaking down a flowing river of data into buckets that can be cataloged and stored. For example:

- An audio signal, with its infinite variations in amplitude, must be sampled at specific intervals and its amplitude mapped to discrete levels.

- An image, representing continuous changes in light and color, is pixelated into finite, numerical values.

This conversion is essential for computation but comes with trade-offs. Quantization introduces approximations; a continuous signal can only be represented with a finite precision, leading to quantization errors. In fact, measure theory states that infinite precision is not achievable, not even in a theoretical setting.

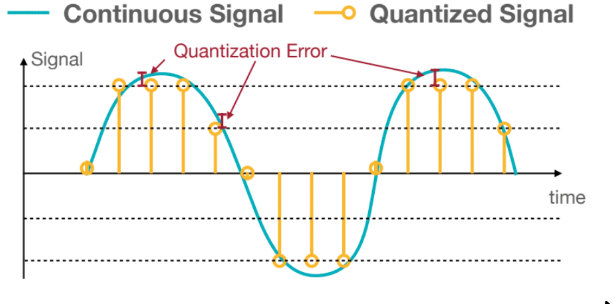

The following image illustrates the process of quantization. First, the signal is sampled at a specific rate, meaning values are selected along the x-axis at regular intervals. Here, we’ll assume the x-axis represents time. On the y-axis, we have the amplitude of the signal, which is then mapped to a finite set of discrete levels.

The difference between the actual signal value and its closest quantized level is known as the quantization error. This error is an unavoidable artifact of the process, stemming from the approximation required to fit continuous values into a discrete framework:

At first glance, you might think this discussion has little to do with machine learning, especially since we’re not directly talking about models. Why should we care about the quantization of real-valued, continuous signals like audio or images? And you’d be partly correct—our primary concern isn’t the raw quantization of these signals.

Instead, the point here is to emphasize the tradeoff between the true value of a signal and its representation within hardware. Neural networks aim to mimic the inner workings of the human brain, which constantly produces electrical impulses and signals. In machine learning, these impulses are represented as neuron activations. However, these activations must ultimately exist within a machine, and machines operate within the constraints of discreteness and finiteness. This means that the continuous signals we’re trying to emulate must be mapped into a discrete, finite set of values.

This is where data types come into play. The choice of data types for representing weights and activations in neural networks is absolutely critical. It impacts not only the precision and accuracy of the computations but also the efficiency of the entire system. And, as you’ll see shortly, the requirements for data representation often differ significantly between the training and inference phases of a model.

Before diving into those differences, let’s take a moment to refresh our understanding of numeric data types and their implications.

Numeric Data Types: The Skeleton of Computation#

Integers: The Bones of Simplicity#

Let’s start with the simplest data type you can think of: the integer.

Representing an unsigned integer is straightforward. Given n, the number of bits used for representation, we simply use the binary representation of the number. Here’s a quick refresher for those who might need it:

In this case, the range of the representation is \([0, 2^n - 1]\).

But what about signed integers? These require a way to handle both positive and negative numbers, and there are two common approaches for this:

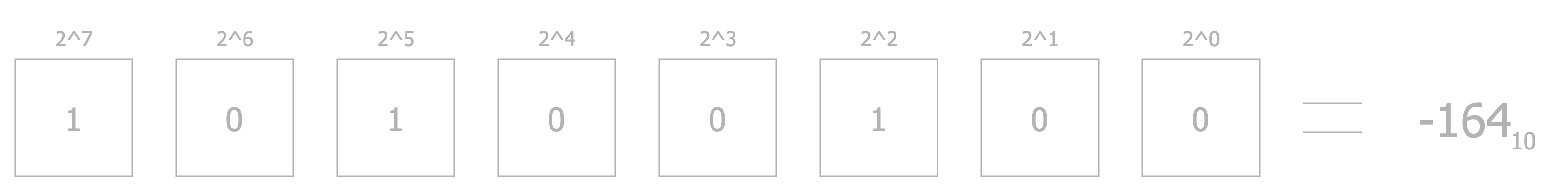

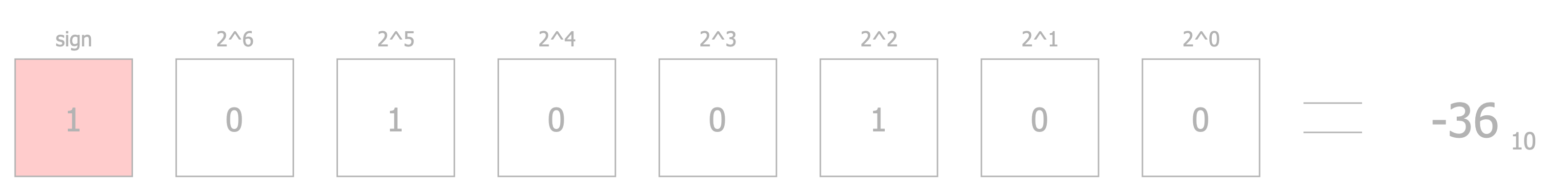

One possible approach is called Sign-Magnitude Representation. In this method, the leftmost bit (most significant bit) represents the sign of the number: \(0\) for positive and \(1\) for negative. The remaining bits represent the magnitude. For example:

In this representation, the range of values is \([-2^{n-1} + 1, 2^{n-1} - 1]\).

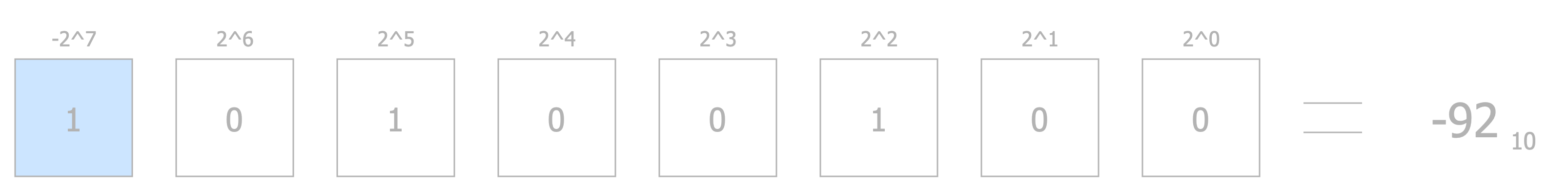

Alternatively, the Two’s Complement Representation can be used. Here, the leftmost bit is treated as having a negative value, allowing for a more elegant way to represent signed numbers. This method is widely used in modern computing because it simplifies arithmetic operations. For example:

With two’s complement, the range of values becomes \([-2^{n-1}, 2^{n-1} - 1]\).

Floating Point Numbers: The Lifeblood of Precision#

Floating-point numbers are where things get interesting—and a little tricky. Unlike integers, they need to represent both whole numbers and fractions, which means we need more complex ways to store them. There are several standards for this, so let’s dive in!

The most common one you’ve probably heard of is IEEE 754, which defines the famous 64-bit and 32-bit floating-point formats, also called FP64 and FP32.

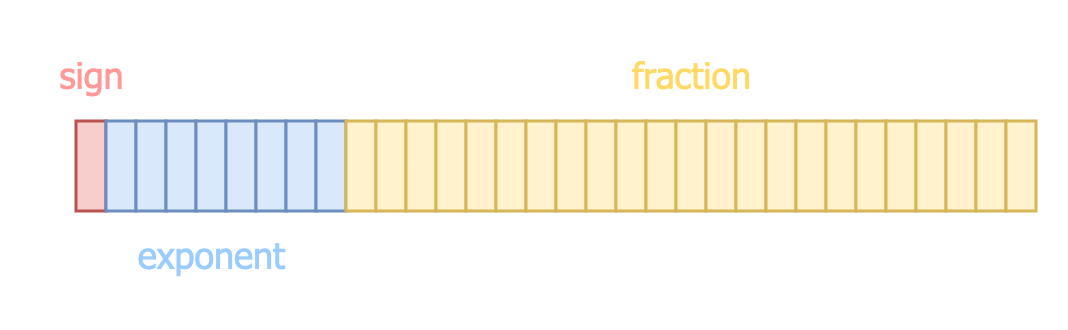

FP64 splits 64 bits into three parts: 1 sign bit, 11 exponent bits and 53 fraction bits (often called the mantissa or significant).

Likewise, FP32 splits its 32 bits into three parts: 1 bit for the sign, 8 bits for the exponent, and 23 bits for the fraction.

Here’s what an FP32 number looks like:

The value of an FP32 number is calculated using this formula: \((-1)^{sign} \times (1+ fraction) \times 2^{exponent-127}\)

Note: Don’t stress about the formula! It’s slightly different for subnormal numbers, but we can skip those for now.

Now, what’s the point of splitting numbers this way? Each part has a job:

- The sign bit is obvious—it tells you whether the number is positive or negative.

- The exponent determines how big or small the number can get, controlling the numeric range.

- The fraction determines the numeric precision.

The kicker is that there’s always a tradeoff between range and precision. With a fixed number of bits, you have to decide what’s more important for your task. Do you need pinpoint accuracy, or do you need to handle really large (or tiny) numbers?

Beyond FP32: Cutting into Smaller Tissue Layers#

FP32 offers a solid balance between precision, speed, and memory efficiency, especially compared to its big sibling, FP64. But here’s the question: do we really need 32 bits for deep learning? As it turns out, the answer is often no. Experiments have shown we can go smaller, and that’s where 16-bit data types come into play.

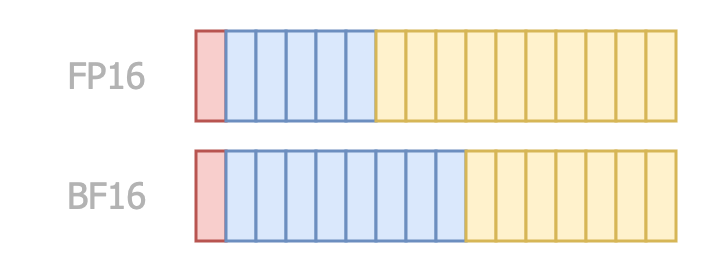

Let’s start with FP16, or “half-precision”. This format uses 1 bit for the sign, 5 bits for the exponent, and 10 bits for the fraction.

This smaller footprint makes FP16 faster and more memory-efficient, which is a big deal for inference tasks where every millisecond counts. However, there’s a catch: those 5 exponent bits don’t provide enough dynamic range to handle the wild swings in gradient values during training. Training a model in pure FP16 often leads to a drop in accuracy because the format struggles to represent very small or very large numbers accurately.

But don’t lose hope! There’s a clever workaround called mixed precision training. The idea is simple: keep the heavy-lifting math (like gradient calculations) in FP32 while using FP16 for everything else. This way, you get the efficiency of FP16 without sacrificing accuracy. We’ll dive into the details of this technique soon.

To address FP16’s limitations for training, Google introduced BF16 (Brain Float 16). BF16 keeps the 8-bit exponent from FP32 but reduces the fraction to 7 bits. This clever tweak gives BF16 nearly the same range as FP32, making it suitable for both training and inference. The reduced precision in the fraction doesn’t hurt much in practice, especially for tasks like training deep neural networks where range matters more than pinpoint precision.

With BF16, you get a sweet spot: less memory usage than FP32 but enough dynamic range to handle training. That’s why it’s become a favorite in the deep learning community.

Even Smaller? Dissecting FP16 and Below#

Why stop at 16 bits? When it comes to efficiency, smaller is better, and researchers are pushing the limits with even tinier formats.

One of the boldest moves is FP8. NVIDIA introduced FP8 to squeeze even more efficiency out of deep learning models. FP8 comes in two flavors: E4M3, using 4 bits for the exponent and 3 for the fraction; E5M2, using 5 bits for the exponent and 2 for the fraction.

If we extend the range to the maximum, we obtain the INT8 data type, which has been a popular choice in the last years.

Both versions focus on maximizing throughput and minimizing memory usage, making them perfect for large-scale inference tasks.

But wait—why stop at 8 bits? Let’s talk about 4-bit formats.

INT4 is a simple 4-bit signed integer. Nothing fancy, but incredibly efficient. This get a bit more interesting with FP4, which comes in variants like E1M2, E2M1, and E3M0, where you can decide how to split the few available bits between the exponent and fraction. These formats are still experimental but hold promise for ultra-fast inference on edge devices and other resource-constrained environments.

Why Do We Care? The Doctor’s Case for Optimization#

All this talk about data types isn’t just academic—it’s mission-critical for machine learning. The data type you choose affects everything: speed, memory usage, and even the accuracy of your models. The key point is that for training, you need formats with enough precision and range (like FP32 or BF16) to capture subtle gradients and updates. For inference, though, you can often afford to go lower (FP16, FP8, or even FP4), with the compromise of losing in terms of accuracy.

Picking the right data type is like choosing the right scalpel in an operating room—you need the perfect balance of precision and efficiency for the task at hand. And trust me, as Machine Learning Surgeons, we always care about the tools we use.

Quantization in Practice: Performing Surgery on Model Precision#

Alright, now that we’ve covered the basics of numeric data types, it’s time to roll up our sleeves and dive into quantization!

In this section, we’ll explore the how, when, what, and why of quantization, starting with a simple explanation and building up from there.

How: Naïve Quantization Algorithms for Quick Fixes#

There are many techniques for quantization, so it would be impossible to cover all of them here. However, let’s focus on building a basic understanding of the process from a mathematical perspective. First and foremost, let’s clarify something: when we quantize a tensor, we aim to reduce its values. Naturally, the values of the quantized tensor will exist in the same dimensional space but within a subset of its co-domain. To put it simply, we shrink the tensor’s values (not its shape!) so that it can be represented using a data type that requires fewer bits.

For example, let’s say we want to quantize a tensor in FP32 format, called \(\mathrm{X}\) into INT8 format—a significant leap! Since we’re targeting the INT8 data type, all the values of the FP32 tensor must be mapped to integers in the range \([-128, 127]\).

Let’s implement a very simple quantization technique called absolute maximum quantization.

Absolute Maximum Quantization: A Straightforward Incision#

The first step is to compute a scaling factor. This factor is calculated by dividing the absolute maximum value of the tensor \(\mathrm{X}\) by the largest representable number in the target data type, which in this case is 127:

\(\mathrm{S}= \frac{max|\mathrm{X}|}{127}\)

Once we have the scaling factor \(\mathrm{S}\), we scale all the values in \(\mathrm{X}\), which we’ll call \(\mathrm{x_i}\) and then round them to get the quantized values:

\(\mathrm{q}_{i}= round(\frac{\mathrm{x_i}}{\mathrm{S}})\)

If any values end up outside the representable range, we clamp them to fall within the range of the target data type.

Reconstructing the original values is straightforward. We just multiply the quantized values by the scaling factor:

\(\mathrm{\hat{\mathrm{x_i}}}= \mathrm{q_i} * \mathrm{S}\)

Of course, the reconstructed values won’t be identical to the original ones due to approximations during the process. This difference is what we call the quantization error, something we touched on earlier.

One final thing to note about absolute maximum quantization: it’s symmetric. This means the resulting tensor values are centered around zero, which is a nice property for certain applications.

Zero-Point Quantization: Accounting for Asymmetric Anatomy#

For certain types of tensors, we can reduce the reconstruction error from quantization by using asymmetric quantization methods, such as zero-point quantization. This approach introduces an offset to account for the asymmetric ranges between the source and target data types, making it particularly useful when the data isn’t centered around zero.

Zero-point quantization is still very straightforward to implement. To begin with, we compute the scaling factor. This factor represents the ratio between the range of values in the source tensor and the range of values that can be represented by the target data type. The computation adjusts for the difference in these ranges:

\(\mathrm{S}= \frac{max(\mathrm{X}) - min(\mathrm{X})}{max\_int - min\_int}\)

Once we have the scaling factor, the next step is to calculate the zero-point, which acts as the offset. This offset ensures that the minimum value of the source tensor aligns correctly with the minimum value of the target data type. The zero-point is determined based on the scaling factor and the range of values in the source tensor:

\(\mathrm{Z}= round(min\_int - \frac{min(\mathrm{X})}{\mathrm{S}})\)

With both the scaling factor and the zero-point ready, we quantize the tensor. Each original value is scaled and then shifted by the zero-point offset to ensure it fits properly into the target data type:

\(\mathrm{q}_{i}= round(\frac{\mathrm{x_i}}{\mathrm{S}}) + \mathrm{Z}\)

Dequantization is just as simple. To reconstruct the original values, you reverse the process: first, shift the quantized values back by removing the zero-point offset, and then re-scale them to their original range. A word of caution here—make sure you shift back the values before applying the scaling factor, not the other way around!

\(\mathrm{\hat{\mathrm{x_i}}}= (\mathrm{q_i} - \mathrm{Z}) * \mathrm{S}\)

By using zero-point quantization, we can better preserve the original tensor’s characteristics, especially when dealing with data that isn’t symmetrically distributed. This method is a handy tool for minimizing quantization errors in such scenarios.

What: Identifying the Organs to Quantize#

Now that we’ve explored a naïve way to perform quantization, let’s discuss what to quantize.

Weights and Activations: The Heart and Brain of Deep Learning#

To begin with, let’s start at a very low level. Most of the computations in deep learning models involve matrix (tensor) multiplications. So, let’s focus on the matrix multiplications between the input tensor \(\mathrm{X}\) and the weights \(\mathrm{W}\). A simple approach to quantization is to quantize the entire matrices. However, remember that the scaling factor depends on the values within the tensors. This means that using a finer granularity can help avoid or limit some potential numerical instability issues.

Consider a scenario where a tensor’s values are sampled from a uniform distribution, but the minimum and maximum values are actually out-of-distribution (i.e., extreme values that don’t represent the typical data). This can cause numerical instability during quantization because the scaling factor relies heavily on these two values.

To address this, we can use per-token and per-channel quantization. This approach involves quantizing a row of \(\mathrm{X}\) and its corresponding column in \(\mathrm{W}\) independently, so that the min and max values are computed at the token or channel level. By doing so, we mitigate the influence of out-of-distribution extreme values, leading to a more stable and accurate quantization process.

Up until now, we’ve discussed quantizing tensors in general terms. However, in the context of deep learning, we must decide whether to quantize the weights, the activations, or both. This decision is important because it affects both the precision of the model and its computational speed. Therefore, it’s crucial to make this choice thoughtfully and with a clear understanding of the trade-offs involved.

When: Choosing the Right Time for Precision Surgery#

Deciding what to quantize is also closely related to when we want to perform quantization.

Static Quantization: Prepping the Patient Before Surgery#

The most straightforward approach is post-training quantization. This involves taking a trained model and applying a chosen quantization algorithm.

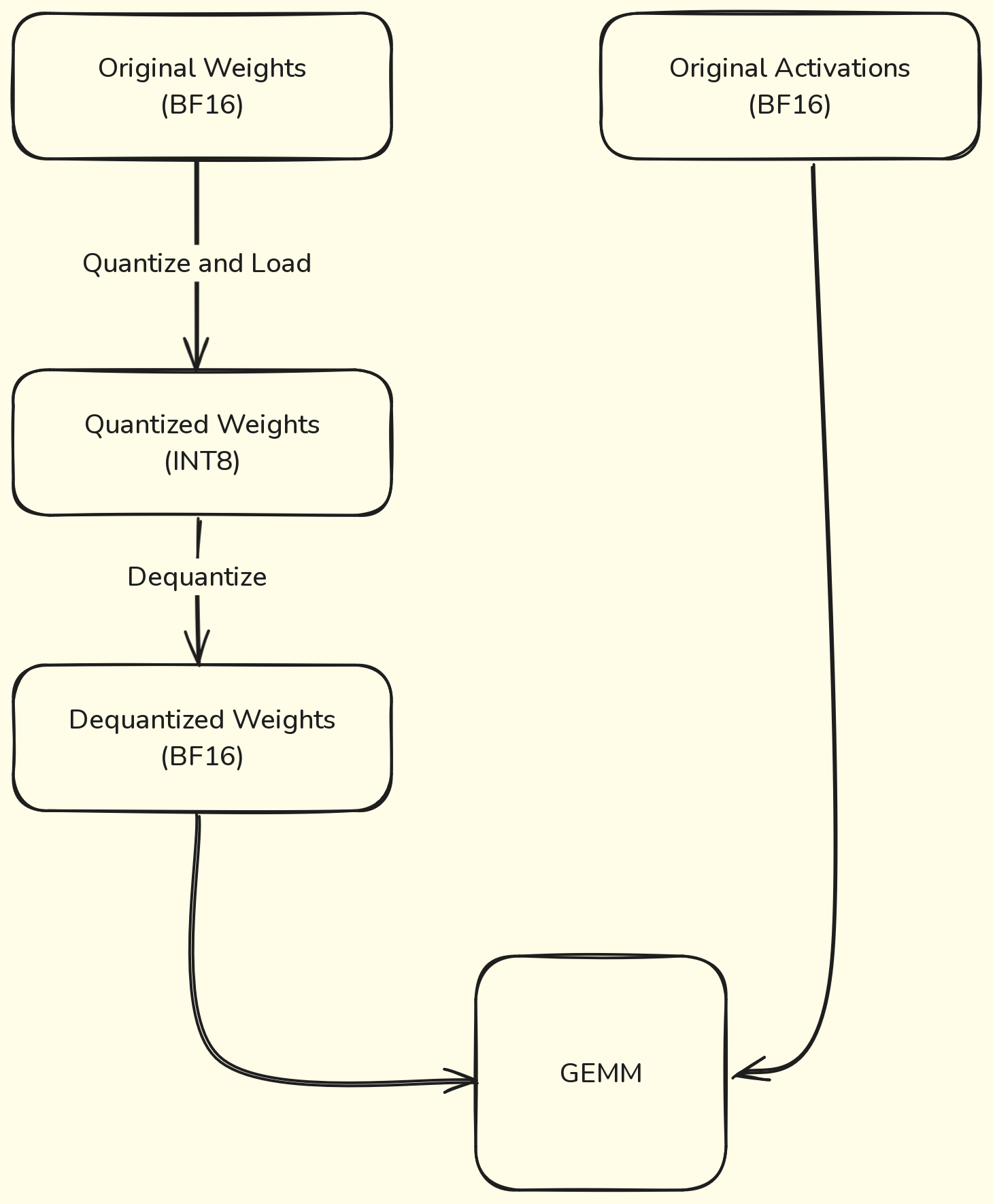

Let’s stop for a second and think about what we can quantize using this approach. We don’t have any particular limitation in this case: we surely can quantize the weights and the model when loading it in memory. However, if we quantize only the weights, the activations of the model will keep their original data type (let’s say BF16). This means that in order to perform the multiplication between the weights and the activations, we must dequantize the weights before that. This adds a significant overhead. At the same time, statically quantize the activations of the model seems kinda impossible, since activations depends on the input, which is only known at runtime, unlike the weights of the model that do not change overtime.

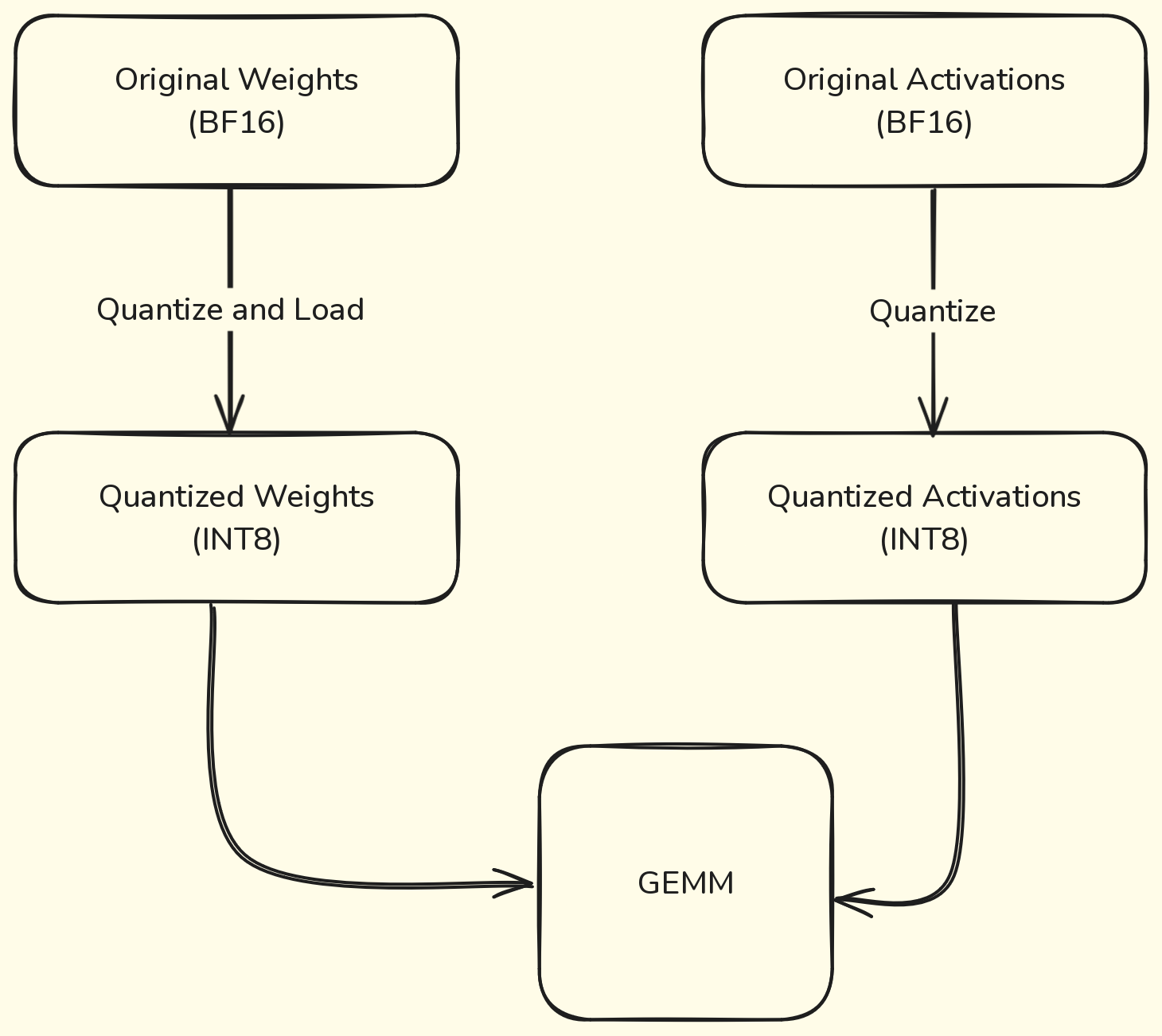

We can actually statically quantize the model’s activations by using a calibration dataset, which will be used to observe the activations of the model and compute their distributions. These distributions are then used to determine how the specifically the different activations should be quantized at inference time. In this way, we avoid the drawback of dequantization for allowing the matrix multiplication.

Here’s a visualization of both cases:

I know what you’re thinking. The first case doesn’t make any sense: why would be quantizing the weights if then we are dequantizing them before doing the GEMM? Trust me, there’s a reason and I’ll explain it in the next section.

Dynamic Quantization: On-the-Fly Adjustments#

This approach applies to static quantization. However, we could also choose dynamic quantization, where activations are quantized on the fly during inference. In this case, there’s no need for a calibration dataset, and the activation quantization becomes more accurate since it isn’t constrained by a pre-computed, limited distribution derived from the calibration data. The tradeoff remains the same: increased latency in exchange for better accuracy.

Quantization Aware Training: Training with Surgical Foresight#

But what if post-training quantization lowers the model’s performance too much? In such cases, we can turn to a more sophisticated technique called Quantization-Aware Training (QAT). This method simulates quantized computations during the forward pass while retaining higher-precision weights during backpropagation. By making the training process aware of the quantization, QAT helps the model adapt to the lower precision of its parameters, resulting in significantly better accuracy retention.

Mixed Precision Training: Balancing Precision and Efficiency#

Since I brought it up earlier, let me briefly explain mixed precision training. As mentioned before, FP16’s dynamic range isn’t large enough to store training gradients with sufficient precision. This limitation means that if we were to train entirely in FP16, we’d likely end up with a poorly performing model. This is where mixed precision training comes in. The idea is straightforward: we start with FP32 weights and then quantize them to FP16 to speed up the inference during the forward pass. This results in FP16 gradients, which are then dequantized back to FP32. By doing this, we maintain numerical stability and avoid troublesome issues like vanishing or exploding gradients—fascinating phenomena to study but undesirable in practice. After that, the process is business as usual. The optimizer step remains unchanged, wrapping up the training cycle with the stability of FP32 and the speed benefits of FP16.

Why: Quantization as the Life-Saving Operation#

Let’s dive into the significant advantages offered by the various quantization techniques we’ve explored. Quantization isn’t just about reducing a model’s memory footprint—though that’s certainly a key benefit. It also unlocks improvements tailored to specific use cases. Understanding these unique advantages allows us to make informed choices about the best quantization strategy for a given scenario.

Dynamic Quantization: Tackling Compute-Bound Emergencies#

Picture this: you’re working with a massive language model (LLM) boasting 70 billion parameters. In such cases, memory becomes the limiting factor, as loading the model’s weights into memory dominates the inference process.

Enter weights-only static quantization. By reducing the precision of the weights, the memory requirements shrink dramatically, enabling faster weight loading. Although there’s some overhead from the dequantization step (necessary for precise matrix multiplications between weights and activations), this tradeoff is well worth it in memory-bound applications.

In essence, static quantization relieves the memory bottleneck, leading to substantial improvements in overall inference performance. See? I told you it’d make sense!

Dynamic Quantization: Tackling Compute-Bound Bottlenecks#

Now, let’s shift focus to dynamic quantization. While it also reduces the memory footprint by utilizing lower-bit precision data types, its real strength lies in speeding up computations. Dynamic quantization dynamically converts weights or activations into integers for matrix multiplications during inference.

Why is this impactful? Integer matrix multiplications are inherently faster than their floating-point counterparts. As a result, dynamic quantization is a game-changer for compute-bound scenarios, where the primary bottleneck is the sheer number of floating-point operations (FLOPs). By quantizing activations and leveraging the speed of integer arithmetic, we can significantly boost performance with only a minor hit to accuracy.

Additional Benefits: Energy Efficiency and Scalability in Healthcare Systems#

Quantization’s benefits extend beyond speed and memory. From an energy efficiency perspective, lower-precision computations consume considerably less power. For instance, a 32-bit floating-point multiplication requires about 3.7 picojoules (pJ), while an 8-bit integer multiplication demands just 0.2 pJ—a more than 18-fold reduction in power consumption! This is particularly advantageous for edge devices and large-scale deployments where energy efficiency is critical.

Scalability also comes into play. Smaller models are inherently easier to handle due to their reduced memory and computational demands. This makes them more suitable for resource-constrained environments and simplifies scaling in production systems.

These considerations are crucial in real-world settings, where the performance of a machine learning system is evaluated not just by its metrics but also by its cost and return on investment. Not every organization can afford to operate like OpenAI, burning millions of dollars daily. For most companies, quantization offers a practical way to achieve high performance while keeping costs manageable.

Quantization in Frameworks: The Surgeon’s Toolkit#

Alright, I’ll stop rambling now. By this point, you should have a solid grasp of what quantization is, the technical details of how it works, the methodologies we can apply, and the scenarios where each approach excels.

Now, let’s roll up our sleeves and dive into how to implement quantization in different frameworks.

Pytorch: The Scalpel for Precise Optimization#

Let’s start simple. PyTorch, as always, is amazing. One of its recent innovations is Torch AO (Architecture Optimization), a framework designed to streamline optimization techniques like quantization. While it’s still in beta, it offers a wide range of quantization options that are already incredibly powerful.

PyTorch supports three primary modes for quantization: Eager Mode, FX Graph Mode, and PyTorch 2 Export. I won’t go into the details here, but you can check out the official documentation for a deeper dive.

Quantizing an nn.Module using Torch AO is straightforward. The library abstracts much of the complexity involved in different quantization methodologies, and most approaches boil down to using the quantize_ function.

This function takes several arguments, with the key ones being the nn.Module to be quantized and a callable apply_tensor_subclass that specifies the quantization type to perform.

For example, if we want to quantize weights to A16W4 (activations in 16-bit and weights in 4-bit), we’d use:

quantize_(model, int4_weight_only(group_size=32, use_hqq=False))

Here, int4_weight_only is the function that applies quantization to the weights. Notice that the function takes two arguments, namely group_size and use_hqq. The Group Size is a nifty trick for improving quantization precision. Smaller group sizes lead to better precision because, as we’ve discussed, scaling factors rely on statistical properties like the minimum and maximum values of the tensor. If the tensor values are widely spread, this can introduce significant de-quantization errors. By dividing the tensor into smaller groups and calculating scaling factors for each, we reduce this error.

HQQ instead stands for Half-Quadratic Quantization, and it’s a method for performing weight-only quantization without requiring a calibration dataset. It’s particularly useful for quick deployment. If you’re curious, you can read more in this this blogpost.

But how does quantize_ know which modules to quantize? That’s where the filter_fn argument comes into play. This callable determines, module by module, whether quantization should be applied. By default, quantize_ only quantizes linear layers using the internal _is_linear function.

Want to try dynamic quantization? It’s just as simple:

quantize_(model, int8_dynamic_activation_int8_weight())

This applies int8 dynamic symmetric per-token activation quantization and per-channel weight quantization.

Torch AO offers many other quantization options, but you get the idea. It’s a versatile and powerful tool that makes implementing quantization in PyTorch easier than ever.

GPTQ: Surgical Innovation in Post-Training Quantization#

GPTQ is a post-training quantization technique that leverages INT4 weights alongside FP16 activations. It builds upon the Optimal Brain Quantization (OBQ) framework, which originally introduced per-channel quantization. However, GPTQ incorporates key optimizations that make the process more efficient and scalable.

For instance, using GPTQ, Bloom 176B can be quantized in under 4 GPU-hours. That’s a remarkable achievement, especially when compared to the original OBQ framework, which required 2 GPU-hours just to quantize a 336M parameter BERT model.

So, how can you apply GPTQ in practice? It’s quite straightforward, especially with the auto-gptq library. Here’s how you can get started:

First, define a GPTQ configuration:

gptq_config = GPTQConfig(bits=4, dataset="c4", tokenizer=tokenizer)

In this example, we specify: the number of bits for weight quantization (e.g., bits=4 for int4) and the calibration dataset (e.g., “c4”).

The configuration can include many other parameters, so I highly recommend checking the official documentation.

Next, load your model with this configuration:

quantized_model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(

model_id,

device_map="auto",

quantization_config=gptq_config

)

And voilà! Your model is ready for deployment with efficient post-training quantization.

Transformers’ LLM.int8(): Mitigating Outliers with Precision Cuts#

By now, you’re likely familiar with the main tradeoff in quantization: dequantization error. This error largely stems from the scaling factor, which is derived from the statistical properties of the tensor being quantized. While techniques like group quantization aim to minimize this error by using multiple scaling factors, Hugging Face’s Transformers library offers another innovative approach: LLM.int8().

The core idea behind LLM.int8() is to tackle the dequantization error caused by outliers. Instead of attempting to quantize every parameter in the tensor, this method separates the outliers—parameters with unusually large magnitudes—and processes them differently.

Here’s how it works. First, outliers are identified based on their magnitude. Anything above a threshold of 6 is considered an outlier. Instead of forcing these extreme values into the quantization process, the method handles them separately in FP16, while the rest of the tensor is processed in INT8. Afterward, the two results are combined—dequantized INT8 data merged with FP16 outliers—to produce the final output.

This approach works brilliantly for large models, especially those with more than 6 billion parameters, where cumulative dequantization errors can wreak havoc as they propagate through layers. By dealing with outliers differently, LLM.int8() ensures much better precision.

The threshold is statically set to 6, therefore parameters with a magnitude larger than 6 will be considered outliers and will not be quantized. Is it a coincidence that the threshold is the same as for ReLU6? If you think about the motivation behind ReLU6, I’d say it’s probably not.

Of course, there’s a catch. Since it performs two separate matrix multiplications, one for the outliers and another for the rest, the method isn’t as fast as FP16. In fact, it’s about 15-23% slower right now, though optimizations are in the works.

So, how do we actually quantize a model to LLM.int8()? It’s pretty straightforward. First, you load the original FP16 or BF16 model as usual. Next, you create a replica using the Linear8bitLt class provided by bitsandbytes. After that, you simply copy the state dictionary from the original model to the quantized one. The magic happens when you move the quantized module to the device—that’s when the actual quantization kicks in. Here’s a quick example pulled straight from the official documentation:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import bitsandbytes as bnb

from bnb.nn import Linear8bitLt

fp16_model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(64, 64),

nn.Linear(64, 64)

)

int8_model = nn.Sequential(

Linear8bitLt(64, 64, has_fp16_weights=False),

Linear8bitLt(64, 64, has_fp16_weights=False)

)

int8_model.load_state_dict(fp16_model.state_dict())

int8_model = int8_model.to(0) # Quantization happens here

Hardware Support: The Operating Table for Modern Quantization#

At the end of the day, all these methodologies and techniques are only as valuable as the practical benefits they deliver. While they might work beautifully in theory, the real-world performance hinges on hardware capabilities. Let’s briefly go over the hardware requirements needed to truly leverage these quantization techniques, and then we’ll wrap this up—this article has gone on long enough!

Tensor Cores, introduced by NVIDIA in 2017 with the Volta architecture, are a game-changer for deep learning. These specialized cores were designed to accelerate matrix operations, the backbone of most deep learning workloads. Over the years, NVIDIA has iterated on Tensor Core technology, adding support for an expanding range of data types with each new GPU generation.

The first generation of Tensor Cores, debuting with the Volta architecture (e.g., the V100), supported FP16 operations. This innovation helped popularize mixed-precision training by making it both efficient and practical.

Next came the Turing architecture, which introduced a second generation of Tensor Cores capable of handling integer operations, including INT8 and INT4.

The Ampere architecture (think A100) further extended support to BF16, enabling even more flexibility for precision-constrained computations.

With the Hopper architecture (e.g., the H100), FP8 was added to the mix, further improving performance for workloads requiring reduced precision. And with NVIDIA’s latest Blackwell architecture, we now have support for FP4, pushing the boundaries even further.

Another critical factor to consider is memory bandwidth. Since quantization reduces the memory footprint of tensors, we need faster cache hierarchies and increased memory bandwidth to efficiently feed Tensor Cores and other low-latency hardware. Without these enhancements, the performance gains from quantization could be bottlenecked by data transfer speeds.

Conclusion: The Final Diagnosis#

Quantization isn’t just a buzzword in the operating theater of machine learning; it’s a surgical technique that enables us to enhance efficiency, scalability, and sustainability in the field. Whether reducing the memory footprint of a sprawling language model or improving computational speed for edge devices, quantization holds the scalpel for optimizing deep learning systems without sacrificing too much accuracy.

Yet, as any seasoned surgeon knows, the tools are only as good as the hands that wield them. Understanding the anatomy of numeric data types, the timing of precision adjustments, and the capabilities of hardware ensures that every cut is calculated. Frameworks like PyTorch and techniques like GPTQ empower practitioners to bring these theoretical innovations to life in their practice.

As we leave the operating room, the prescription is clear: quantization is no longer an optional refinement—it’s a fundamental step in building systems that are not only powerful but also efficient, affordable, and environmentally conscious. For every aspiring surgeon of machine learning, this technique is not just a tool—it’s the future.